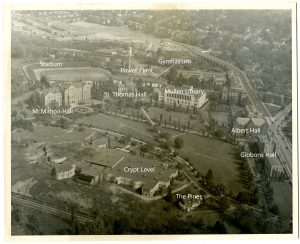

Catholic University of America Aerial View

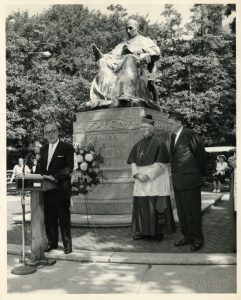

Posts with the tag: Catholic University

The Special Collections of Catholic University is home to many valuable labor collections. Prominent among these are the papers of Terence V. Powderly, John Mitchell, John Brophy, and Phillip Murray. Less well known, but no less impactful, are the papers of Chicago natives Harry C. Read and Joseph Daniel Keenan (1896-1984). The latter is the subject of this blog post. Referred to by biographer Francis X. Gannon as 'Labor's Ambassador,' the talented, modest, and patriotic Keenan was a labor leader who was an important labor-government liaison during the Second World War, a significant force in labor's post war support for Democratic presidential candidates from Harry S. Truman to George C. McGovern, and a key advisor to George Meany, long-time leader of the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO).

Born in 1896, Keenan was the eldest of eight children. He left school at an early age to help support his family after his father was injured and he became an electrician by trade. He participated in the labor movement in Chicago, beginning with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers' (IBEW) Local 134 in 1914, and then from 1937 as Secretary of the Chicago Federation of Labor. In 1940, he moved to Washington, DC, to work with President Franklin Roosevelt's National Defense Advisory Commission to mobilize national defense in the face of Hitler's European onslaught. He eventually became the Vice Chairman for Labor of the War Production Board, 1943-1945, where he worked effectively to stabilize industrial relations in the construction field and to halt strikes and work stoppages while arbitration agreements were conducted. He served in postwar Germany, 1945-1948, as both an advisor to American commander General Lucius D. Clay and as President Truman's special coordinator between labor and industry for reorganizing trade unions.

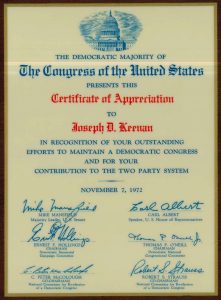

Keenan returned home for the 1948 elections where he was first director of the League for Political Education where he was credited with an important role in Truman's upset victory over Thomas Dewey. He later served as labor's campaign liaison with presidents John F. Kennedy (1960) and Lyndon B. Johnson (1964), Vice President Hubert Humphrey (1968), and Senator George McGovern (1972). He served as first Secretary of the Building and Construction Trades Department of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), 1951-1954, and IBEW International Secretary, 1954-1976. He was a key friend and advisor to George Meany when the latter merged the rival AFL and CIO into one organization in 1955 and Keenan served thereafter as Vice President and Executive Council member of the combined AFL-CIO.

Keenan was an active Catholic layman and was honored with the papal medal, Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice Award, in 1973 and an honorary doctorate from The Catholic University of America (CUA) in 1974. For the latter, Catholic University stated "Like his patron and fellow craftsman, Joseph the Carpenter, he richly deserves the title 'Justus Vir.'" He was also a recipient of the Medal of Merit and Medal of Freedom by President Harry S. Truman for World War II services. Keenan was known to support civil rights organizations and helped found the Joint Action in Community Service (JACS), the political organization behind Jobs Corps that trained millions of disadvantaged, including minorities, for employment. [1] He was also devoted to the State of Israel. He was married three times, first to Ethel Fosburg, by which they had son Joseph Jr; second to Mytle Fox, whose son John was adopted by Keenan; and third to Jeffie Hennessy. His burial mass in 1988 was held at Holy Name Cathedral in Chicago. For more information on Keenan, see his papers at Catholic University and a 1971 oral history transcript at the Harry Truman Library.

[1] Francis X. Gannon. Joseph D. Keenan, Labor's Ambassador in War and Peace. Lanham, New York, and London: University Press of America, 1984, p. 155.

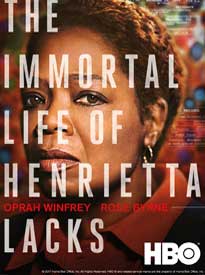

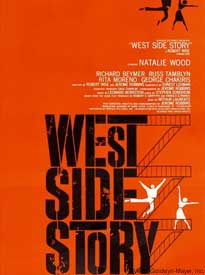

Do you enjoy streaming and watching movies? We are happy to announce a new streaming service Swank Digital Campus!

This streaming library includes 1,000 top feature films, documentaries and foreign films from the largest movie studios, including Walt Disney, Warner Bros., Paramount, NBCUniversal, Columbia Pictures, Lions Gate, MGM, Miramax and many more.

Feature films include Casablanca , Psycho , West Side Story , Jaws , Blazing Saddles , E.T. The Extra Terrestrial, Beauty and the Beast, and Jurassic Park . Documentary-dramas include Won't You Be My Neighbor? and The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. Click here to see more titles using the Swank Featured Collection.

Please click here to access and select STUDENT.

Google Chromecast allows users to stream directly to their TVs. Please visit Google's support pages at the link for information on setting up your Chromecast device. See Google Chromecast support and setup.

Happy Watching!!

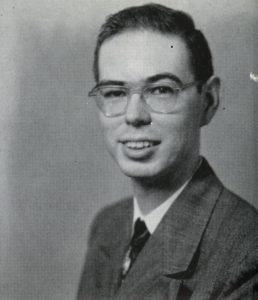

Morris J. MacGregor (1931–2018), who died three years ago this month, was a native Washingtonian and an alumnus of The Catholic University of America. Over his lifetime he served both his country and his church; as a dedicated and fearless historian, he documented the tangled record of both the United States Army and the Roman Catholic Church on the tortured subject of race relations. I was acquainted with him first and foremost in my capacity as an archivist who provided him access to primary source materials for his research and writing. But he was also a friend who mentored me in my own historical writings and who gave me very sage advice at a crucial time on how best to face my wife's terminal cancer prognosis.

MacGregor was born on October 11, 1931 in Washington, D.C. to Morris J. MacGregor, Sr. (1903–1979), a paper salesman, and Lauretta Cleary MacGregor, a homemaker. He grew up in nearby Silver Spring, Maryland, and attended the now defunct Catholic boy's school at Mackin, the old St. Paul's Academy, in Northwest Washington. He earned his bachelor's in 1953 and his master's in 1955, both in History, from Catholic University, and also studied at Johns Hopkins University, 1955–1959, and the University of Paris on a Fulbright Scholarship, 1960–1961. He was an affiliate of the U.S. Army Center of Military History in Washington, D.C., 1959–1960. He then served as an historian of the Historical Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington, 1960–1966, then as Acting Chief Historian of the U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1966–1991.

One of his books, The Integration of the Armed Services, 1940–1965 (1981), received a commendation from then-Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberg and is still considered an authoritative account of this sensitive subject. In it, MacGregor addresses how the military moved from reluctant inclusion of a few African Americans to their routine acceptance in a racially integrated establishment. This process was, he argues, part of the larger response to the civil rights movement that challenged racial injustices deeply embedded in American society. MacGregor's book also explores the practical dimensions of integration, showing how the equal treatment of all personnel served the need for military efficiency. His other military studies include two edited works with Bernard Nalty—the 13-volume Blacks in the Armed Forces (1977) and Blacks in the Military: Essential Documents (1981)—as well as Soldier Statemen of the Constitution (1987), co-authored with Robert K. Wright, and The United States Army in World War II: Reader's Guide (1992), co-authored with Richard D. Adamczyk.

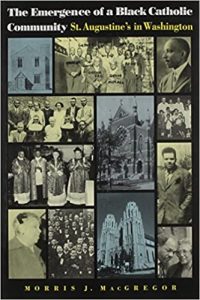

A practicing Catholic, MacGregor authored several books on American Catholic History, including The History of the John Carroll Society, 1951–2001 (2001), published by the John Carroll Society in Washington, D.C., and three published by Catholic University Press. The first was A Parish for the Federal City: St. Patrick's in Washington, 1794–1994 (1994). St. Patrick's is the oldest Roman Catholic parish in Washington, D.C., witnessing the city's evolution from a struggling community into a world capital. As Washington's mother church, MacGregor argues it transcended the usual responsibilities of an American parish; its diverse congregation has been pivotal in shaping both national policies and the history of the Catholic Church in the United States. The second was The Emergence of a Black Catholic Community: St. Augustine's in Washington (1999), which presented in detail the history of race relations in church and state since the founding of the Federal City. MacGregor relates St. Augustine's from its beginning as a modest chapel and school to its development as one of the city's most active churches. Its congregation has included many of the intellectual and social elite of African American society as well as poor immigrant newcomers contending with urban life. The third was Steadfast in the Faith: The Life of Patrick Cardinal O'Boyle (2006), an account of the churchman responsible for the racial integration of D.C. Catholic Schools as well as a driving force in Catholic Charities.

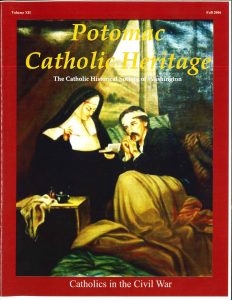

MacGregor was a member for many years of the Catholic Historical Society of Washington, D.C., serving as co-editor and contributor, along with friend and fellow Catholic University alum Rev. Paul Liston, of the Society's quarterly glossy magazine, Potomac Catholic Heritage (previously the Society's Newsletter), 2005–2015. Issues of the publication are archived in the Special Collections at Catholic University along with many records that were central to MacGregor's research on the American Catholic Church, especially in relation to African Americans (see our research guide on African American History Resources).

March is Women's History Month, so why not celebrate a pioneering woman who was an historian: Catherine Ann Cline, distinguished scholar of Great Britain in the twentieth century and former chair of the History Department at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. She was especially interested in the rise of the British Labour Party and the roots of the British appeasement of Fascism in the wake of the controversial Treaty of Versailles that ended the First World War. Cline was also a gifted teacher of erudition who mentored many students as well as being a lover of the arts. Her archival papers are among those of many notable History department faculty along with those from other disciplines at Catholic University housed in Special Collections.

Cline was born on July 27, 1927 in West Springfield, Massachusetts, to Daniel E. Cline and Agnes Howard. She earned a B.A. from Smith College in 1948, an M.A. from Columbia University in 1950, and a Ph.D. from Bryn Mawr College, where she worked with Felix Gilbert. She taught at a number of universities between 1953 and 1968: Smith College, St. Mary's College of Indiana, and Notre Dame College of Staten Island. In 1968, Cline became an associate professor of history at Catholic University and rose to full Professor in 1974. She served as Chair of the History Department from 1973 to 1976 and again from 1979 to 1982. Noted for her integrity, and in recognition of her long service to Catholic U she was awarded the Papal Benemerenti Medal on April 10, 1995, Catholic U's Founders Day. She continued teaching at CUA until her death in 2006 after a long illness.

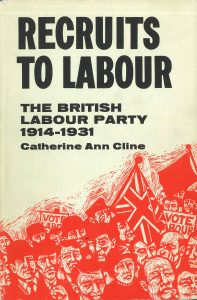

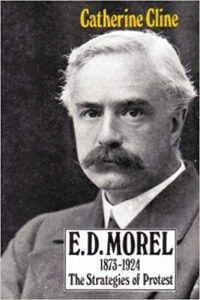

Cline was an expert in modern British history, especially the early twentieth century and the rise of the Labour Party. She was the author of the book Recruits to Labour: The British Labour Party, 1914-1931 (1963). It was an innovative prosopography of nearly seventy political converts in the era of the First World War who reshaped Labour's domestic and foreign policy in the postwar environment. Cline's second book, E. D. Morel, 1873–1924, The Strategies of Protest (1981), is an authoritative political biography of an outspoken reformer who demanded democratic control over British diplomacy. He was jailed during the war by the British government for his anti-war activism.[1] Morel is also notable for defeating Winston Churchill in the 1922 Parliamentary election, taking Churchill's Scottish seat in Dundee and effectively knocking Churchill out of the Liberal Party. Churchill only found has way back into Parliament later as a Conservative.

Cline's third area of research, published in articles in The Journal of Modern History and Albion and presented in papers at scholarly conferences, examined British public opinion and the Treaty of Versailles. Seeking the roots of British appeasement, she uncovered ways that British elites promoted a negative view of the peace treaty and their impact on interwar diplomacy. She also wrote numerous articles and book reviews for the American Historical Review, Catholic Historical Review, and Church History. Additionally, she was a research fellow of the American Philosophical Society and a member of the Faculty Seminar on African History at Columbia University as well as a member of the American Historical Association, the American Catholic Historical Association, and the Conference Group on British Studies. She served on several prize committees of these organizations.[2]

Her former colleague and distinguished professor of British history in his own right, Dr. Lawrence Poos, described Cline as:

"Cathy Cline was instrumental in my being hired as a faculty member in the History Department, and what I remember of my first impression of her is what remained throughout her career here and after her retirement: personally and professionally she was gracious, in an old school sense (and I mean that as a most sincere compliment). Even when she was strongly opposed to something, she would find the right occasion to make her opinions clear in the proper setting. She was also famous for the New Year's breakfast (really, brunch) she hosted in her apartment each year, in homage (so we always understood) to the famous salon-style breakfasts and conversations of Victorian Prime Minister William Gladstone."[3]

In conclusion, while I only met her briefly a few times on campus, I was most impressed by her first published work, before she emerged as a scholar of modern Britain, which was an excellent 1952 article [4] on the coal fields of eastern Pennsylvania, a subject near and dear to my heart. It always struck me that the gain to British labour history was a loss to American labor history!

[1] Carole Fink, February 1, 2006. American Historical Association web site- https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/february-2006/in-memoriam-catherine-ann-cline

[2] Ibid.

[3] Poos to Shepherd, email, March 3, 2020.

[4] Cline, Catherine Ann. 'Priest in the Coal Fields, The Story of Father Curran,' Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia, Vol. 63, No. 2 (June 1952), pp. 67-84.

While walking across campus, have you ever looked up? The first residents of campus are still present, peering down…

Since the very opening of the University, every generation of Cardinals has studied and graduated under the watchful eyes of Caldwell Hall. And we do mean eyes, as the exterior of the building has been home to dozens of stone faces since the opening of the building in 1889. Walking along the west side of the façade, you can find numerous "grotesques" peering out. Grotesques, similar to gargoyles, are stone faces adorning a structure. While gargoyles are specifically designed to serve as water spouts, grotesques primarily decorative.

While we have little information on why the designs on Caldwell were selected, we do know that on March 9, 1888, the Baltimore-based architectural firm of Baldwin and Pennington contracted the stonework of the building to Bryan Hanrahan. Presumably Hanrahan made the decisions on the designs himself, likely with consultation with University officials. But as is often the case with gargoyle or grotesque designs, the artist may have drawn inspiration from the faces, stories, and peoples that surrounded them.

While we can't say for sure what inspirations there may have been for any of the visages, this author has a sneaking suspicion that one of the faces was inspired by then-President Grover Cleveland. After all, Cleveland did attend the cornerstone-laying of Caldwell Hall in 1888, giving ample opportunity for the artist to see him up close (and providing a connection to the building).

There are perhaps too many faces – both inside and outside – of Caldwell to catalog in one blog post! But some of the highlights include an figure sticking out their tongue and a person hiding behind a book (see the image at top). While the interior of Caldwell may appear more dignified, with only a few stern faces holding up the columns in the main stairwell, the exterior is a "grotesque" landscape!

But Caldwell is not the only ornamented structure on campus – several other buildings have design features that may be missed at first glance. Look closely at McMahon Hall for the ornate stone vine work that traces the building. Or the next time you pass by the doorway into Mullen Library, look for the Zodiac symbols that grace its entrance (just one of many engravings on the library's exterior). You will even find figures looking out across campus in and on numerous other buildings on campus – some of which this author may not even be aware of! There is hardly enough room in this post to detail them all, but perhaps you can explore a sample of them yourself via a scavenger hunt by following this link.

And do share any faces you find hidden among the stones! Learn more about one alumnus, Jay Hall Carpenter, and his own work with sculpture and grotesques at the National Cathedral in this Mullen Library exhibit!

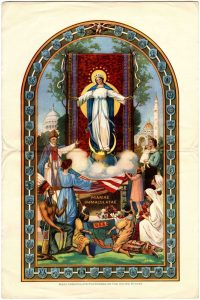

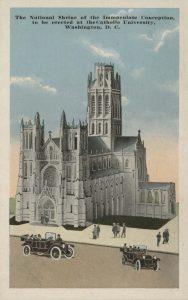

This week marks one hundred years since the foundation stone for the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception was laid on September 23, 1920 . But, like Rome, the Shrine wasn't built in a day. In this blogpost, I'll focus on the early history of the Shrine—from its inception up until the intermission in its construction beginning in 1931.

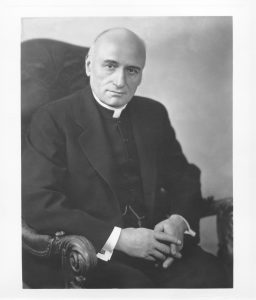

"IDEA MANY YEARS OLD" pronounced the Salve Regina Press , the publisher of the Shrine's fundraising bulletin, on August 1, 1924 ; a fter the Blessed Virgin Mary, under her title of the Immaculate Conception, had been designated as the patroness of the United States in 1847, whispers of a "fitting architectural symbol of this dedication" supposedly occurred at the Second Plenary Council of the Catholic Church in 1866 and surfaced again at the Third Plenary Council in 1884. The establishment of a national Catholic university in 1887 only lent urgency to the matter of a patronal church. When The Catholic University of America first opened in 1889, the campus community patronized the chapel in Caldwell (then-known as Divinity) Hall. As early as July 1910, Thomas Joseph Shahan, the fourth rector of the University (1909–1928), expressed his desire for a full-fledged University Church: "Professors and books shed a dry light," he explained (himself a professor), "but a glorious Church sheds a warm emotional, sacramental light" (Letter to Mr. Jenkins). Dubbed the "Rector-builder," Shahan championed much of the campus construction in those days—perhaps to a fault: "A university is a society of men, not buildings," chided his successor, Monsignor James H. Ryan (Nuesse 171; Malesky 90). In any case, the Shrine was his pride and joy. In 1913, Pope Pius X gave Shahan his blessing along with $400 (Tweed 49).

By at least one account , the fact that the foundation stone arrived in one piece for the festivities seven years later was a miracle; it was driven more than 1,500 miles from New Hampshire down to Washington, D.C. (taking a very winding path) on the back of a new-fangled green and gold "Auto Truck" whose brakes supposedly failed at one point during the journey. The donor of the stone, James Joseph Sexton, remarked "how lucky we were to travel so far […] without accident," adding "I shall always reverence the Blessed Virgin Mary as I have told many […] how she protected us at Perryville Road when our Auto Truck dashed down the hill at fully 40 miles an hour" ("On This Day in History").

Cardinal James Gibbons , Archbishop of Baltimore, presided over the laying of the foundation stone—as he had on numerous other occasions at the University (including the inaugural event on May 24, 1888, when the cornerstone of Caldwell Hall was laid). The next day, The Washington Post described the ceremony as "one of the most notable religious events ever witnessed in the National Capital," and reported that "10,000 persons thronged the university campus to view the spectacle" ("Vast Shrine Is Begun"). But conspicuously absent from the crowd that day were some of the Shrine's earliest and most ardent supporters: laywomen like Lucy Shattuck Hoffman who made up the National Organization of Catholic Women (NOCW) (Tweed 35).

Hoffman had played a prominent part in the prehistory of the Shrine (between 1911 and 1918), not only as the founder of the NOCW but also as the mother of an established architect who in 1915 submitted the " plaster model of Gothic design " pictured in many of the Shrine's early promotional materials (Tweed 32). As such, Hoffman apparently took for granted the fact that her son would get the commission. But in 1918, the University's Board of Trustees decided to abandon the Gothic in favor of a Romanesque design. For whatever reason, the devoted members of the NOCW were not made privy to the Trustees' decision and were left instead to read about it in the same fundraising periodical they helped distribute (Tweed 33). Hoffman felt betrayed. The members of the NOCW's New York chapter resigned in solidarity, and just like that, one of the first national organizations of Catholic women "abruptly disbanded" (Tweed 34).

Interestingly, the foundation stone was laid "only thirty-six days after women won the right to vote," but the climate at the ceremony was not celebratory (Tweed 17). In his sermon that afternoon, the bishop of Duluth accused women of "seeking a freedom that is excessive" ("Vast Shrine Is Begun"). His apparent lack of support for women seems incongruous given that the Shrine was not only marketed explicitly to "America's Marys," but was also in large part the product of women's fundraising efforts.

In the absence of any traditional American ecclesiastical style, the architectural firm Maginnis and Walsh felt that "the U.S. cultural condition allowed—even demanded—freedom to experiment" (Tweed 25). Hence the "Byzantine beach ball" we know today (Tweed 5). Some have suggested that Shahan and the architects rejected a Gothic design because the National Cathedral , already underway in the District of Columbia, was Gothic. Others have suggested that they sought an alternative design because Gothic structures took too long to build—an ironic objection, considering the Shrine was only completed "according to its original architectural and iconographic plans" upon the dedication of the Trinity Dome mosaic in 2017: four score and seventeen years after the foundation stone was laid in 1920 ("Dedication of the Trinity Dome").

Construction on the crypt level did not actually begin until three years later, in 1923. The first public Mass was held in the crypt church on Easter Sunday in 1924. Later that year, the Salve Regina Press reported: "In this crypt, incomplete though it is, already ordinations have been held and thousands of pilgrims have attended Mass, often said while the hammers of workmen punctuated the singing of the priest" ("Glories of the Crypt"). Presciently, the closing paragraph of the same August 1, 1924 issue of the Salve Regina Press exactly predicts future delays: "When the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception will be completed is as much a problem as the great cathedral-builders of the Middle Ages faced. Business depressions, wars—many things—may intervene."

For years, Shahan and his secretary, the Reverend Bernard A. McKenna, were the "two master minds" of the Shrine project, but shortly after Shahan's death in 1932, McKenna—the Shrine's first director—returned to his pastoral work in Philadelphia (Tweed 29–30). The loss of leadership was compounded by the onset of the Great Depression and the United States' eventual entry into WWII; the project lay dormant after the crypt level was completed in 1931.

For more than two decades the lower church evoked the "Half sunk" Ozymandias ; at one time, the bishop of Reno complained that it "remained a shapeless bulk of masonry half-buried in the ground" (Tweed 42). Following a 23-year hiatus, construction resumed in 1954 and the superstructure was formally dedicated on November 20, 1959 . For more on that story, stay tuned for the centennial in 2059!

Although the foundation stone isn't visible from the outside, you can see it by visiting what is now the Oratory of Our Lady of Antipolo, or #17 on the page-two map from this 1931 guide book .

Works Cited

"Dedication of the Trinity Dome," https://www.nationalshrine.org/history/#timeline.

"Glories of the Crypt," The National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception (Salve Regina Press, August 1, 1924). Thomas Joseph Shahan Papers. Collection 69, Box 39, Folder 6.

"Idea Many Years Old." The National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception (Salve Regina Press, August 1, 1924). Thomas Joseph Shahan Papers. Collection 69, Box 39, Folder 6.

Letter to Mr. Jenkins, dated July 28, 1910. Thomas Joseph Shahan Papers. Collection 69, Box 39, Folder 6.

Malesky, Robert P. The Catholic University of America. Arcadia, 2010.

Nuesse, C. Joseph. The Catholic University of America: A Centennial History. CUA Press, 1990.

"On This Day in History," September 23, 2019, https://www.nationalshrine.org/blog/on-this-day-in-history-the-laying-of-the-basilicas-foundation-stone/

Tweed, Thomas A. America's Church: The National Shrine and Catholic Presence in the Nation's Capital. Oxford, 2011.

"Vast Shrine Is Begun," The Washington Post , September 24, 1920. The National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception Collection. Collection 48, Box 9, Folder 1.

Guest blogger, Professor Árpád von Klimó, of The Catholic University of America History Department teaches Modern European and World History at the University. He has done research in different fields of Modern and Contemporary European history. Most recently, he has edited the Routledge History of East Central Europe (together with Irina Livezeanu) and published two monographs: "Hungary since 1945" (Routledge, 2018) and "Remembering Cold Days. The Novi Sad Massacre, Hungarian Politics and Society since 1942" (Pittsburgh UP, 2018).

His research on Father Dennis is part of a broader project related to the history of the University's History Department. He sees this history as a mirror of the past of an institution that has always profited from a fruitful tension between church and world, between priests and laymen. This story has not been told yet but this project seeks to tell it, in the process providing us with profound insights into the identity of the University, knowledge essential for its future. Since 2015, student apprentices, faculty, and archivists have begun to compile, sort, publish, and analyze archival materials related to the department of history, its professors and students. This project is part of a new program of undergraduate apprenticeships in history (course HIST 494) in which students learn practical research, analytical, editorial and publication skills. Throughout this course, students learn how to manage unexplored mines of "big data," to hone research and writing skills, and in the process gain insights into how many generations have experienced life and learning on this campus.

***

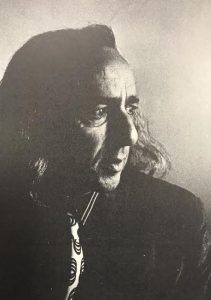

In the 1971 yearbook of The Catholic University of America (the University was informally referred to as "C.U." at the time), a quotation accompanied the photo of Jesuit Father George T. Dennis, representing the History Department:

"The Speech and Drama Department represents about all that the rest of the city knows about CU. The University plays little or no role in the development of the community, yet it has facilities, leadership potential, and a great deal more to offer. 'Neutrality' is only the position of some administrators and, as is fairly obvious, does not represent the feeling of the University's faculty or students. If the University does not loudly let its real stand on vital issues be known, it might as well relocate to some remote spot on the planet."[1]

Father Dennis spoke about the necessity and duty of the University to be present in the District and to be actively engaged in helping to solve its political and social problems. These were immense after the riots and political turmoil of the Vietnam Years and in the wake of the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy. He would do his part, teaching urban youth for many years, while teaching Byzantine and Medieval History and doing research as a renowned scholar. Obituaries in The Catholic Historical Review and The Dumbarton Oaks Papers have talked about his scholarly achievements and mentioned his activities with urban youth of Washington, D.C.

George T. Dennis was 44 years old when he came to Catholic University in 1967 from Loyola University, Los Angeles, to work as editor of the Corpus Instrumentorum Inc. , while teaching Byzantine History at the department. The Corpus was an international encyclopedic project, based on the re-organized staff of the New Catholic Encyclopedia (published until 1967), which was housed on the campus of the University between 1967 and 1971. [2] When the enterprise fell apart, Father Dennis became a full member of the department which took over his salary which had been mostly paid by the Corpus project.

The case of Father George T. Dennis also shows how a professor of the University could follow his academic career as a famous historian of Byzantium and be an activist on- and off-campus at the same time. When he complained about the "neutrality" of the administration on questions of social injustice in his quotation for the 1971 Yearbook, he also expressed his conviction that the majority of the faculty and the students were with him in regard to social activism and the metropolitan community.

In the fall of 1970, Father Dennis was elected to head the Neighborhood Planning Council (NPC) for Northwest Washington where he lived in a small community of Jesuits. The NPC was organizing programs to help struggling youth in the area and negotiated with the DC government to improve their situation. Father Dennis jokingly declared that he preferred "to proportion his life between the Northwest Area and the Byzantine Empire." In 1971, Father Dennis as head of the NPC, protested the declaration of a curfew in the city. Read more about Father Dennis, the NPC , and the curfew in the November 19, 1971 issue of The Tower (p.4).

On theological questions, Father Dennis came out as a "dissenter" who, in 1968 together with the theologian Charles Curran (who later left the University), publicly criticized Pope Paul VI's Encyclical Humanae Vitae . Read more on this in The Tower, April 18, 1969 (p.10)

Later, in the mid-1980s, Father Dennis, spoke out against what he saw as the politicization of the church; he was especially critical of some bishops' engagement in campaigns against abortion. See his September 22, 1984 letter to The Washington Post for more.

Eight years later Father Dennis criticized the founding of a library that served as predecessor to the Saint John John Paul II National Shrine, accusing him of having been "consistently hostile to genuine academic spirit and practice." See more in the See more in the November 20, 1992 issue of The Tower (p. 6).

Father Dennis, indeed, could never have been suspicious of "neutrality" which he thought was the position of "a few administrators" of the university, as he said in 1971. But his critique of what he thought went wrong in church and society, was not his main mission. He was an active reformer who tried to help the most vulnerable members of society. When he engaged with struggling inner-city youth, he did this without revealing his own scholarly and priestly background. The teenagers he helped with their homework and with their day-to-day problems, called him simply "George", and "he preferred it that way", as one obituary stated. [3]

Dr Matina McGrath, who teaches at George Mason University, was a graduate student of Father Dennis. She remembers him as an "academic mentor and a dear friend." [4] As others, Dr McGrath was impressed by his humility: "One would never know the depth of his scholarly interests or the reputation he had among his Byzantine colleagues if he just met him hurrying to class, winded from riding his bike, straightening his hair. He loved to make his undergraduate classes fun, and was pleased beyond words when he figured out how to incorporate sounds and images in his power point presentations (I can still see him smile when he told me he had lions roaring when he showed a rendering of the imperial throne with all its mechanical contraptions). Even before electronic media, he would show up to class with bits of chain mail, helmets, miniature soldiers and siege equipment to liven up the lessons on Byzantine History. Without a doubt he was one of the most popular professors in the history department at CUA." [5]

One of his last wishes was to donate his scholarly library to the Ukrainian Catholic University of Lviv, another sign of his wide-spread interests and his giving personality.

[1] Catholic University of America '71 Yearbook, Washington, DC: CUA Press, p. 134.

[2] Choice, February 1979, 1560.

[3] Email from Dr. Lawrence Poos, 7 July 2020.

[4] Email from Dr. Matina McGrath to author, 9 July 2020.

[5] Email from Dr. Matina McGrath to author, 9 July 2020.

On July 13, 2020, the Washington Redskins announced that they would finally be retiring the team name—a move that the team's owner, Dan Snyder, had repeatedly resisted, perhaps most vehemently in 2013. His exact words: "We'll never change the name. […] It's that simple. NEVER — you can use caps."

Controversy over the team's name and logo stems not only from the term "redskin" but from the use of American Indian iconography in mascots, in general. My own high school in Montgomery County, Maryland— Poolesville High School —used the Indians as its mascot from 1911 all the way up until 2002, when the community's vote to keep the problematic mascot had to be overruled by the county's Board of Education; at that time Poolesville reluctantly adopted the Falcons as its new mascot. The term "redskin," meanwhile, has been likened to the N-word: a term denoting skin color which through years of derogatory use has become offensive. Wikipedia has an entire page devoted to the Washington Redskins name controversy; it traces the dispute back to the 1960s, when it was presumably raised in connection with the Civil Rights Movement.

Since the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, however, calls for racial justice have been falling less on deaf ears. Dr. Maria Mazzenga, Curator of the American Catholic History Research Center, sees the reconsideration of the team name as part of a broader "historical consciousness shift generated in part by Floyd's murder and the demonstrations that followed"; the reconsideration came about in earnest after the @Redskins participated in #BlackOutTuesday on June 2 , at which time others were quick to call out the team's hypocrisy. A team with a racial slur for a name had no leg to stand on when it came to standing against racism, critics argued.

Located in the nation's capital, The Catholic University of America (CatholicU) has a short but momentous history with the Washington, D.C., NFL (National Football League) team. Established in Boston as the Braves in 1932, the football team was renamed the Redskins in 1933; the new name was devised to help avoid confusion with a local pro baseball team (which was also called the Braves) without giving up the reference to indigenous Americans. In February of 1937, the Redskins relocated to Washington, D.C., where the CatholicU Redbirds were enjoying a heyday.

In his centennial history of Catholic University, C. Joseph Nuesse refers to the arrival of athletic director Arthur J. "Dutch" Bergman in 1930 as the beginning of "a new era" (Neusse 274). Under Rector James H. Ryan and Dutch Bergman, ""Big time" intercollegiate football became a prime objective of the university's athletic program" (Neusse 274). According to CatholicU alumnus and local historian Robert P. Malesky, "Bergman was paid a higher salary than any faculty member, causing considerable consternation, though his winning record over his decade at the school caused an equal amount of joy" (Malesky 91).

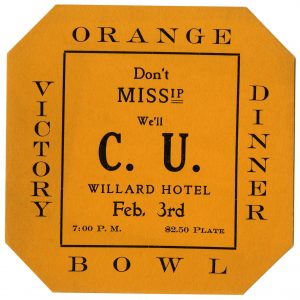

On New Year's Day, 1936, the CatholicU Cardinals narrowly defeated Ole Miss in the second-ever Orange Bowl (the first was held on January 1, 1935). The score was 20–19. Malesky describes the game as a nail-biter: "CUA jumped out to a 20–6 lead, but then Ole Miss came back strong, scoring 13 points late in the game. A missed point after a touchdown for Mississippi was the critical difference" (Malesky 92). At the helm was Bergman. The 1936 yearbook also lists the Assistant Backfield Coach as recent alumnus Thomas Whelan —a star athlete who entered Catholic University in 1929 on a football scholarship and who upon graduation (in 1932) played professionally for the Pittsburgh Pirates, soon-to-be Steelers. Incidentally, Whelan and Bergman also teamed up off the field; between 1936 and 1938, the two ran a tavern together in the Brookland neighborhood adjacent to the CatholicU campus.

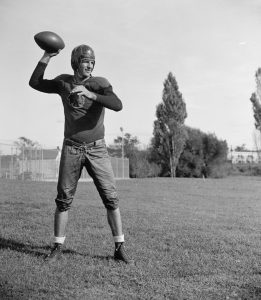

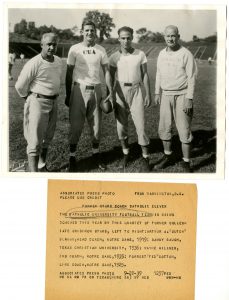

A 1939 photograph shows the thickset Bergman standing alongside his assistant coaches in the CatholicU stadium, which had been dedicated in 1924 under Rector Thomas J. Shahan and which was situated more or less in the area now occupied by the Pryzbyla Center and the Columbus Law School. The two coaches standing in the center of the photograph were contemporary "stars with the Washington Redskins football team": quarterback "Slingin'" Sammy Baugh—a "future hall of famer" —and Wayne Millner, an offensive and defensive end who had played for Notre Dame before going pro (Malesky 91). According to Malesky, "Baugh was not a full-time coach but did come out a few afternoons during the season to instruct CUA's quarterbacks" (Malesky 91). The fourth man in the photograph is Forrest Cotton, another Notre Dame alumnus. Of course Bergman was himself a noted alumnus of the Fighting Irish . Standing about five feet eight inches tall and weighing 145 pounds, he earned the nicknames Little Dutch and The Flying Dutchman for his quickness. His roommate was the legendary George Gipp, a fact which he joked would overshadow any of his own accomplishments.

In CatholicU history, Bergman goes down as the "all-time winningest varsity football coach" and to this day holds "the highest winning percentage (.649) in school history" ( McManes ). According to the same article from CatholicAthletics.com , "CUA dropped football in 1941 because of the outbreak of World War II and didn't field another team until 1947." In that interim, Bergman went on to coach the Redskins in the 1943 season (at which time Sammy Baugh was still quarterback). In 1948, Bergman became the manager of the D.C. Armory—the corporation that lobbied for the construction of RFK Stadium in Washington, D.C. At the time of his death in 1972, Bergman was still managing the D.C. Armory and RFK Stadium. As Washington Post sports writer Bob Addie mused, "The handsome silver-haired man who died Friday night (August 18, 1972) got his wish—he never retired."

Works Cited

Brady, Erik. "Daniel Snyder says Redskins will never change name." USA TODAY Sports. https://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/nfl/redskins/2013/05/09/washington-redskins-daniel-snyder/2148127/. May 9, 2013. Accessed July 20, 2020.

Malesky, Robert P. The Catholic University of America. Charleston, SC, Arcadia Publishing, 2010.

McManes, Chris. "Former coach Dutch Bergman distinguished himself in all walks of life." Catholic University Cardinals. https://www.catholicathletics.com/sports/fball/2012-13/releases/dutch_berman_feature_story. December 14, 2012. Accessed July 20, 2020.

Neusse, C. Joseph. The Catholic University of America: A Centennial History. Washington, D.C., The Catholic University of America Press, 1990.

The novel coronavirus pandemic has left record numbers of Americans jobless—inviting comparisons between now and the Great Depression almost one hundred years ago. The Archives at the Catholic University of America (CatholicU) is well positioned to offer a historical perspective on current events. Two particular collecting strengths from the Depression era, relating to Catholic views on government and entertainment, crisscross the economics and culture of the period—and resonate in our own day.

Following the stock market crash of October 1929, the United States plummeted into an economic depression from which it would not fully recover until the onset of World War II. In 1933, unemployment peaked at 24.9% and Franklin Delano Roosevelt assumed the office of the president. In 1935, he signed the Social Security Act—introducing among other things the unemployment insurance program from which some 40 million Americans are currently seeking relief in the wake of "the unprecedented wave of layoffs" triggered by the pandemic. On the morning of Friday, June 19, 2020, The New York Times reported that, for the thirteenth week in a row, more than one million unemployment claims were filed.

The American Catholic History Research Center and University Archives holds the papers of several Catholic supporters of FDR's New Deal programs, including Patrick Henry Callahan , Francis Joseph Haas , John O'Grady , and John A. Ryan —who was nicknamed "Right Reverend New Dealer." The digital exhibit Catholics and Social Security recounts the active role that Catholic Charities played in shaping New Deal legislation and the Social Security Act in particular. Importantly, though, the CatholicU Archives also document the activities of Catholic detractors of the New Deal—most notably Charles Coughlin. The Social Justice Collection consists of the weekly publication of the National Union for Social Justice (N.U.S.J.), which served as Coughlin's political vehicle. Another digital exhibit, Catholics and Politics: Charles Coughlin, John Ryan, and the 1936 Presidential Campaign , details the conflicting views of the two Catholic priests on FDR's (first) reelection campaign.

Meanwhile, against the backdrop of the worst economic crisis in U. S. history dawned the Golden Age of Hollywood. The fact that moviegoing actually spiked during the Depression has been cited amidst other financial meltdowns: during the Great Recession of 2008 , for instance. The phenomenon is commonly rationalized in one of two ways: escapism or catharsis. No doubt entertainment has served similar ends during the COVID-19 pandemic, but it has found a new mode of delivery—skipping theaters altogether. After a long spring of streaming from the safety of the sofa, will the appetite for the big screen return?

Back in 1933, as the popularity of moviegoing grew, the church hierarchy's concerns—mostly about the portrayal of sexuality and crime (especially the glorification of gangsters)—also grew. In response, the church founded the Legion of Decency . The Legion was ultimately subsumed into the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) Communications Department/Office of Film and Broadcasting (OFB), for which the CatholicU Archives serves as the official repository. The OFB records include about 150 boxes of film reviews and ratings for movies released from the 1930s onward.

One such movie has recently come back under scrutiny: Gone with the Wind (1939). The highest-grossing movie of all time, the star-studded epic set in the American South has routinely been criticized for perpetuating harmful stereotypes of Blacks. Heeding calls for racial justice incited by the murder of George Floyd, the subscription streaming service HBO Max temporarily took down the controversial classic in June 2020.

Gone with the Wind happens to be historically important to the Legion of Decency. When it was re-released in 1967 (having been reformatted from the standard 35mm into the wider 70mm film stock), it became the first movie for which the Legion (then known as the National Catholic Office for Motion Pictures, or NCOMP) changed its rating "without any alterations in the motion picture" [1]. For this, the President and CEO of MGM was "particularly grateful"; he welcomed the new A-II rating (morally un objectionable for adults and adolescents) and jumped to the conclusion that "the cloud around this classic has been removed" [2].

Upon its release in 1939, Gone with the Wind had been rated B (morally objectionable in part, for all). The Legion's objections: "The low moral character, principles[,] and behavior of the main figures as depicted in the film; suggestive implications; [and] the attractive portrayal of the immoral character of a supporting role in the story [which is to say, the prostitute]" [3]. Referring to the original objections—including "the famous use of the word "Damn" by Mr. Gable"—one Catholic reviewer wrote, "By the standards of 1967, these elements are rather harmless" [4]. But other elements not originally objected to had since (at the height of the Civil Rights Movement) become top-of-mind, as they have again today [5]:

One moral factor however which must be considered which did not seem quite so obvious years ago is the attitude of the film toward the South, slavery, and the negro. […] The slaves are presented as being content with their lot. […]

This is a ridiculous and immoral attitude, and not fair—we are shown the plantations but not the slave quarters. […] In view of this I recommend the Office reclassify the film AIII, for Adults, and that some observation be made on our attitude toward the treatment of the Negro in the film.

For more about Catholics and the Great Depression, please see the newly-launched research guide: Special Collections — Great Depression Resources .

Notes

[1] "NCOMP Upgrades Rating of 'Gone With The Wind'," Times Review, LaCrosse, Wis., September 15, 1967. OFB Reviews, Collection 10, Box 51, Folder 55.

[2] Letter from Robert H. O'Brien to Father Patrick J. Sullivan, September 1, 1967. OFB Reviews, Collection 10, Box 51, Folder 55.

[3] Letter from Mrs. Eva Houlihan, Secretary to Right Reverend Monsignor Thomas Little of the Legion of Decency, to Reverend Hilary Ottensmeyer, O.S.B., November 13, 1964. OFB Reviews, Collection 10, Box 51, Folder 55.

[4] and [5] "Gone with the Wind: Screened-Friday, May 5, 1967," Rev. Louis I. Newman. OFB Reviews, Collection 10, Box 51, Folder 55.

This August will mark the one hundredth anniversary of the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, which states that no citizen of the United States shall be denied the right to vote "on account of sex."

The history of women's suffrage is closely allied with the abolitionist and the temperance movements of the early 19th century—antebellum struggles in which women figured prominently (especially women guided by religious principles). In the aftermath of the Civil War, women's suffrage gained momentum, but its activists were divided among several rival organizations: most notably, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). The 1890 founding of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) braided the NWSA and AWSA together—presenting a united front that propelled women's rights agitation into a mass movement. Arguably, though, the more radical National Woman's Party (NWP)—which was formed in 1916 and made the controversial decision to continue picketing the White House despite the war effort—played the decisive role in getting a constitutional amendment passed.

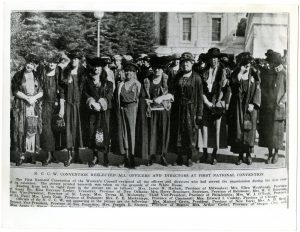

If the zeitgeist of the Progressive Era (1890-1920) was the coalescence of social, political, and economic reform movements into bureaucratic organizations, then women's suffrage embodied it. Not coincidentally, many organizations of Catholic laywomen also trace their roots to the turn of the 20th century. The Catholic University of America (CUA) Archives is the official repository for several prominent organizations of Catholic laywomen, including the Christ Child Society (1887, chartered in 1903 ), the Daughters of Isabella (1897), the Catholic Daughters of the Americas (1903), the National Conference of Catholic Charities (1910), the International Federation of Catholic Alumnae (1914), and the National Council of Catholic Women (1920).

Although Christian goodwill informed much of the moral impetus behind reforms of the Progressive Era, that Christianity was often of a decidedly Protestant variety. The 19th and early 20th centuries were marked by fierce prejudice against Catholics , which was only exacerbated by the dramatic uptick in Irish, Italian, and Polish immigrants in the 1890s. The upshot: Catholics mirrored the wider trends of the Progressive Era in their own sphere.

The Catholic University of America (CUA) has direct ties to three of the above-listed organizations of Catholic laywomen. Brief overviews follow in chronological order.

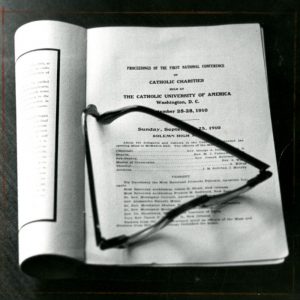

The National Conference of Catholic Charities—today's Catholic Charities USA—was founded on the campus of Catholic University in 1910. As Dr. Maria Mazzenga, Curator of the American Catholic History Research Center, notes in this 2017 blog post , "Catholic laywomen dominated the early membership."

The International Federation of Catholic Alumnae (IFCA), founded in 1914, was headquartered in Washington, D.C. on the campus of CUA until the 1960s. Upon the completion of the IFCA finding aid in 2013, University Archivist and Head of Special Collections W. J. Shepherd explained IFCA's "deep connections to Catholic University as benefactors"—most notably through the endowment of the St. Elizabeth Ann Seton Chair in Education.

Meanwhile, the National Council of Catholic Women (NCCW) ran the National Catholic School of Social Service between 1921 and 1947—a women's school which was officially folded into the men's school at CUA after many years of parallel association. As we commemorate the centenary of women winning the vote, the NCCW , established in 1920, is also celebrating its one hundredth anniversary.

For more on Catholic women, please see the research guide Special Collections — Catholic Women Resources.

Catholic University of America Aerial View

Source: https://www.lib.cua.edu/wordpress/newsevents/tag/catholic-university/

0 Response to "Catholic University of America Aerial View"

Post a Comment